A few years ago, I was checking into an inn somewhere in the New Mexican desert after eight or twelve hours of driving from the Grand Canyon. Pretty tired and looking like this, I was counting down the seconds before I could lie down when someone behind me excitedly recognized me...sort of. "Hey! I'm from Hawaii, too!" she called out. "Oh, cool," I said, "Wow, I can't believe I'm meeting someone from Hawaii way out here." Then after a beat, I wondered, "Wait, how do you know I'm from Hawaii?" She pointed down to my feet, and we laughed, knowing that only a local would wear Locals slippers. That got me thinking. Slippers, a cultural icon, are one of the few quality products actually manufactured in Hawaii. The Locals slipper, arguably at the top of its class, outperforms virtually all other rubber slippers I have known, not only domestically, but internationally as well. Where did they come from?

Elsewhere, they're called flip-flops or thongs, but to anyone from Hawaii, they are only known as slippers. From weaving the leaves of native plants to pouring rubber into molds, here is a look at how the design of slippers - arguably the most culturally significant symbol of Hawaii from the local perspective in modern history - has changed over the years in Hawaii.

|

| Kamaa maole in plan view (looking down from above) as shown in this book (1906). |

The earliest footwear in Hawaii was probably the kamaa maole (Hawaiian sandal; probably today it would be written kama'a maole). Older writings called this invention a sandal and reported it was made out of whatever fibrous plant material that was readily available: lau hala (leaves of the Pandanus tectorius tree), la'i ki (Ti leaf; Cordyline fruticosa; Dracaena terminalis), ili hau (bark of the hau tree, Hibiscus tiliaceus), lau maia (banana leaf), or wauke (Broussonetia papyrifera, the tree prized for making kapa or tapa cloth; poaaha, i.e., wauke leaves).

|

| Tall and slender wauke plants in the foreground, darker green leafy ti leaf plants behind it. Photo credit: Forest and Kim Starr. |

|

| Hala tree and fallen leaves. |

These sandals were made for walking over rough a'a lava. This type of lava is known to completely destroy modern shoes, so it is certainly understandable that ancient Hawaiians would have devised some sort of foot protection for traversing these lava fields. Someone writing about "A Trip to the Volcano" in 1886 reported that his guide carried an extra piece of leather to make new sandals from when the lava inevitably wore his out. Sandals made of wauke or maia were comfortable for walking on coral reef, a similarly abrasive surface.

|

| "A Trip to the Volcano" published March 31, 1886 in The Daily Bulletin, via Library of Congress. |

|

| Rough a'a lava (right) adjacent to smooth pahoehoe lava (left). Pahoehoe lava is much easier to walk on! |

From the 1800s onward, people from various places around the world immigrated to Hawaii to work for sugar cane and pineapple plantations. One place these plantation workers came from was Japan. The first Japanese to arrive enmasse on the Honolulu shore made the journey across the Pacific in 1868 aboard the ship "Scioto", but it wasn't until 1885 that workers from Japan began to really immigrate.

These Japanese brought with them many different types of traditional footwear: geta (wooden clogs), waraji (straw sandals), tabi (heavy cotton socks), and zori (sandal). It is the zori from which modern Hawaii slippers are thought to have derived from.

Of the four footwear types, the zori most closely resembles the modern rubber slipper. Geta are elevated off the ground by blocks of wood, waraji are coarsely woven and look more like the primitive Hawaiian kamaa, and the sock-like tabi lacks straps (they more closely resemble modern neoprene dive boots, although the design distinctively separates the big toe from the others).

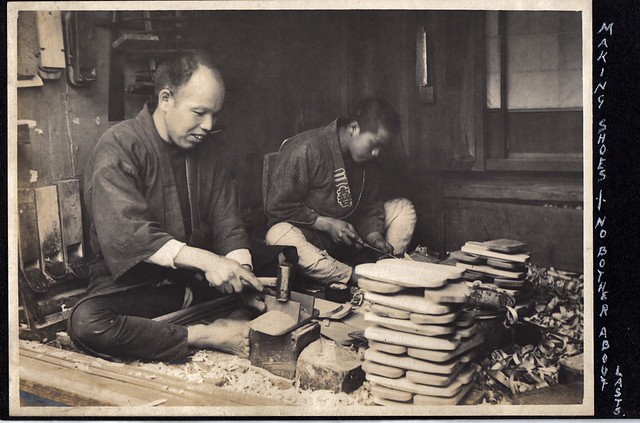

|

| Making geta in Japan, ca. 1914 to 1918. Photo credit: A.Davey. |

|

| Waraji. Photo credit: mrhayata. |

|

| Modern straw sandals, zori. Photo credit: mrhayata. |

|

| Modern tabi. There are many different styles, and they appear to have evolved over the years. I've seen tabis in Hawaii in past decades that look much different than these and others one might find in Japan. Tabis in Hawaii are increasingly scarce. Photo credit: akaitori. |

The zori is a centuries-old, flat-soled sandal with a thong upper designed to pass between the first two toes. In other words, it's a lot like a slipper. Perhaps dating as far back as the Heian Period (794-1192), the sandals have been made of many types of materials throughout history, including straw (including bulrush and rice stalks), bamboo, and cloth.

Wikipedia traces the introduction of rubber zori to the U.S. back to the World War II era but provides no source for this claim. Modern rubber was invented by Charles Goodyear in 1839. Before Goodyear, the material properties of rubber were unstable, melting in the summer and hardening in the winter, leading to bankruptcies in the rubber industry as customers complained. Goodyear's son introduced rubber to the footwear industry*, and devised a way to make shoes to fit the left and right feet. Shoes of the past, including Japanese sandals like the zori, were straight last: they could be worn on either foot due to their lengthwise symmetry (modern Japanese sandal designs are still straight last). Goodyear merged his company with some of his competitors in 1892 to form the U.S. Rubber Company, which invented the world's first sneaker in 1917, Keds. No wonder Americans wearing sneakers stick out like sore thumbs in London: sneakers are as American as apples. The same year Keds hit the market, Converse released the rubber-soled All-Stars shoe that would become famous as Chuck Taylors.

|

| Modern Keds. Photo credit: Leo**. |

Scott Hawaii may have been the first slipper manufacturer in Hawaii. Elmer and Jean Scott, a shoemaking couple from Massachusetts, moved to Hawaii and started making boots for sugar cane and pineapple plantation workers in 1932. During the depression, rubber inner tubes from used tires were recycled into beach footwear under the leadership of Palama Settlement. Tires were recycled to support the war effort in the 1940s, limiting material availability and causing the Scotts to shift their business focus away from plantation boots to casual footwear, namely slippers. They say this is how slipper manufacturing in Hawaii got started.

Island Slipper opened in 1946 in Kaka'ako, a once poverty stricken Honolulu outskirt turned industrial park that is today a burgeoning district increasingly known for its hipster vibe and youthful art scene thanks to gentrification. Originally focusing on quality Asian sandals for women, founders Takizo and Misao Motonaga modified the straight last design of the Japanese zori to make slippers for one's left and right feet, just as Goodyear, Jr. had done for shoes.

Kiyoto Uejio opened The Slipper House (1952-2013), a store exclusively specializing in slippers, in 1952 on Young Street in Honolulu back when there was a Sears there (and later a police station). When he moved his shop in 1959, the same year Hawaii became a U.S. state, The Slipper House became an original tenant at Ala Moana Center, one of the longest tenants in the shopping mecca until 2013 when its lease was not renewed. Uejio sold rubber slippers and upscale woven slippers imported from Japan in its early days. In 1959, the most expensive slippers at the Ala Moana shop cost about $2 (about $16.50 in 2016 dollars), while the rubber slippers cost eighty-five cents ($7 in 2016 dollars).

The first non-skid bottom was introduced in the 1960s, the traction cut by hand or razor. Molds were eventually introduced to eliminate the tedious work (rubber would be poured into the mold, which would probably imprint the outsole design into the rubber).

Hawaii slipper manufacturers have credited San Luis Obispo, California based Beachcomber Bill's with the idea of upgrading the slipper strap design from rubber to nylon in the late 1970s. This innovation crossed the Pacific back to Hawaii and has been around ever since.

When the Motonagas were ready to leave the slipper business, they sold Island Slipper to John Carpenter, a ten year veteran at Scott Hawaii. Carpenter immediately introduced rubber slippers to the Island Slipper product line. With the 2016 opening of their storefront in the new 'Ewa Wing of Ala Moana Center, they are the new Slipper House.

Island Slipper and Scott Hawaii still manufacture higher-end slippers on Oahu today. A pair of slippers at the Island Slipper store in Ala Moana can cost as much as $80, and one of its styles is now carried at J.Crew.

The same year Carpenter became a business owner, Glenn Hada opened Zori Zori in Waipahu. Zori Zori was one of the largest rubber slipper manufacturers in Hawaii as of 1999, and owns the iconic Locals brand (aptly named, you really aren't a local without them). In 1999, Hada was selling 200,000 pairs of rubber slippers a month, 180,000 of them in Hawaii.

Many slipper options out there may excel at beauty, comfort, or long-term durability, but Locals are the Volkswagen Beetle of tropical footwear: economical, practical, well designed, and easy to fix if necessary. Locals slippers are waterproof (there are other brands that are not!), can traverse nearly any terrain, weigh almost nothing, and float. With inferior rubber slipper designs ubiquitous from Fiji to Africa, it's a wonder why Locals hasn't gone global. No matter how many other slippers you own, there is always room for a pair of Locals. The style of the J.Crew Rio combined with the rubber fabrication and function of Locals would be a dream come true for anyone that hasn't yet earned their lū'au feet.

Sources or more reading:

Japanese Immigrant Clothing in Hawaii, 1885-1941 by Barbara F. Kawakami, 1993.

"Rubber feet" by Paula Rath. Honolulu Advertiser, 5/4/99.

"Rubbah Sleepah" by Charles Memminger. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 11/18/92.

"The strides in footwear" by Vicki Viotti. Honolulu Advertiser, 3/10/92.

"rubba slippas" by Linda Tagawa. Honolulu Advertiser, 12/13/97.

"Engineering feat" by Nadine Kam. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 6/26/08.

Also, see links above.

If you have any information to share about slipper design or manufacturing, please consider reaching out by leaving a comment.

__________________________

* Others may have used rubber to make footwear before Goodyear, but Goodyear, Sr.'s discovery of vulcanization was revolutionary.